Slowing down

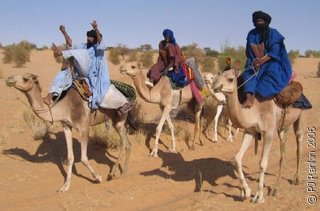

The following morning sees an early start after the last chance for any proper wash for at least a week. 16-legged transport is already folded down on the sand behind the hotel Bouctou, surrounded by bags around which cluster the Tuaregs whom we will get to know well in the next few days: Mohamedune our guide and herder, young Mohamed our earnest interpreter, Al Hadana the cameleer clown and Omar who seems to have come along for the ride to Essakane. We'll be carrying quantities of the strong Chinese green tea and sugar (10kgs of sugar for each 1 kg of tea) that is the essence of Tuareg hospitality, as presents for the encampments we will visit on the way.

OK, it's partly apprehension from previous prolonged and intimate encounters with the hard wooden saddles (a small cushion is a good idea to have in reserve for the soft Westerner), but this morning walking feels good exercise after the 4x4. So heading out westward, our party sets off. It's hardly a trek this time, more a 6 day stroll stopping to visit Tuareg encampments en route with only 70km to cover, which we would have done in 2 or 3 long days if we were back on the salt caravan trail. Well, it's not quite a stroll, as you need to walk 4 - 5 mph to keep up with the camels. Rapidly I remember to take a route over the hardest sand and shorten my stride where it's soft. The locals have a highly-developed, constant speed 'soft sandle shuffle' which minimizes slippage and wasted effort: their footprints are always cleaner than mine.

OK, it's partly apprehension from previous prolonged and intimate encounters with the hard wooden saddles (a small cushion is a good idea to have in reserve for the soft Westerner), but this morning walking feels good exercise after the 4x4. So heading out westward, our party sets off. It's hardly a trek this time, more a 6 day stroll stopping to visit Tuareg encampments en route with only 70km to cover, which we would have done in 2 or 3 long days if we were back on the salt caravan trail. Well, it's not quite a stroll, as you need to walk 4 - 5 mph to keep up with the camels. Rapidly I remember to take a route over the hardest sand and shorten my stride where it's soft. The locals have a highly-developed, constant speed 'soft sandle shuffle' which minimizes slippage and wasted effort: their footprints are always cleaner than mine.

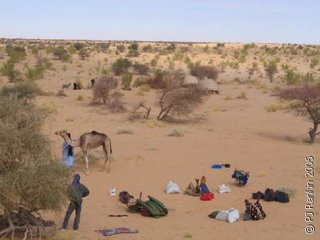

A few hours later and it's time for a lunch siesta in whatever tiny piece of shade that can be found in the heat of the day and for talking and snoozing. Saddles and bags are taken off the four camels, set free to wander off and graze. It's always seems a bit strange, the things are taken off the camels and left right there - one place in the desert is, after all, as good as any other. They've a saying, 'The camel has to eat but the thorns can blind its eye' - a nice way to put everything worthwhile carries a risk.

A few hours later and it's time for a lunch siesta in whatever tiny piece of shade that can be found in the heat of the day and for talking and snoozing. Saddles and bags are taken off the four camels, set free to wander off and graze. It's always seems a bit strange, the things are taken off the camels and left right there - one place in the desert is, after all, as good as any other. They've a saying, 'The camel has to eat but the thorns can blind its eye' - a nice way to put everything worthwhile carries a risk.

Time too for the Tuareg tea ceremony: three cups of the sweet caffeine-jolts of strong Chinese green tea, lovingly made in the traditional small blue enamel teapot over a tiny charcoal brazier that's carried on the side of the saddle. Making tea is essential desert hospitality for Tuaregs to greet strangers or open any meetings. The tea-maker takes great care and pride in the whole process, sipping samples of the brew, pouring it back into the pot, until finally with a flourish he pours out the gold nectar from a great height into three tiny glass cups for the critical palates of those present. Cups are passed round on a silver platter in a strict order of seniority, to be taken in the right hand, drunk quickly and with suitably appreciative noise, then passed back for people waiting. Subsequent rounds are made later by adding even more sugar to the brew. The first round of tea 'as bitter as death' from the pot packed with tea leaves starts the exchange of pleasantries and news, whilst the second, 'as sweet as life' marks the opening of more serious matters and the final round 'as sugary as love' signals closure and time to depart.

Time too for the Tuareg tea ceremony: three cups of the sweet caffeine-jolts of strong Chinese green tea, lovingly made in the traditional small blue enamel teapot over a tiny charcoal brazier that's carried on the side of the saddle. Making tea is essential desert hospitality for Tuaregs to greet strangers or open any meetings. The tea-maker takes great care and pride in the whole process, sipping samples of the brew, pouring it back into the pot, until finally with a flourish he pours out the gold nectar from a great height into three tiny glass cups for the critical palates of those present. Cups are passed round on a silver platter in a strict order of seniority, to be taken in the right hand, drunk quickly and with suitably appreciative noise, then passed back for people waiting. Subsequent rounds are made later by adding even more sugar to the brew. The first round of tea 'as bitter as death' from the pot packed with tea leaves starts the exchange of pleasantries and news, whilst the second, 'as sweet as life' marks the opening of more serious matters and the final round 'as sugary as love' signals closure and time to depart.

Whenever Tuaregs are sitting around talking, their hands seem to be continually sketching to mark and illustrate the conversation or just to doodle patterns and play in the pure fine, free-flowing sand.

Whenever Tuaregs are sitting around talking, their hands seem to be continually sketching to mark and illustrate the conversation or just to doodle patterns and play in the pure fine, free-flowing sand.

With all the new places and busy experiences of Burkina Faso, the first day of walking in the low dun-coloured dunes past occasional acacia thorn trees, I'm thinking I must be a bit crazy, there's nothing to do here! Later, as the days past the silence of the desert fills you. Your senses open up. You see, feel and hear the small things, slow down and get into the rhythm of desert travel on foot or rocking on camelback, enjoy the sunrises, sunsets and evening campfires and feel quiet inside, small in the landscape. Essakane feels like an interruption by the time we get there - you just want to keep on going towards the sunsets until you arrive in Mauritania.

Sandy's wife prepares a big bowl of rice with a few pieces of meat that we share around a small fire that night, eating with right hands. The soft talking in Tamasheq, punctuated with glasses of tea, goes on long into the night, until on invisible signal everyone goes to bed. Suddenly in a couple of minutes the whole camp is silent and everyone else is asleep. Yes, I definitely do need a sleeping bag against the bitter cold of a desert night! A hardy scrap of a desert girl will just scoup out a hole in the sand, cover herself in her black robe and sleep soundly in tight ball, wrapped in the utter silence and roofed by a blaze of stars that reach right down to the horizon. The stars! With all the light pollution from houses, roads and airports in England, you can rarely see the firmament. By day here the desert to the horizon dwarfs travellers, by night the heavens. People are humbled - doesn't our spirit need to experience such places?

Sandy's wife prepares a big bowl of rice with a few pieces of meat that we share around a small fire that night, eating with right hands. The soft talking in Tamasheq, punctuated with glasses of tea, goes on long into the night, until on invisible signal everyone goes to bed. Suddenly in a couple of minutes the whole camp is silent and everyone else is asleep. Yes, I definitely do need a sleeping bag against the bitter cold of a desert night! A hardy scrap of a desert girl will just scoup out a hole in the sand, cover herself in her black robe and sleep soundly in tight ball, wrapped in the utter silence and roofed by a blaze of stars that reach right down to the horizon. The stars! With all the light pollution from houses, roads and airports in England, you can rarely see the firmament. By day here the desert to the horizon dwarfs travellers, by night the heavens. People are humbled - doesn't our spirit need to experience such places?  Morning breaks on the daily problem of finding 4 camels, which may by now be 5km or more away after their night of browsing. The less the vegetation, the further away they will be. I'm still amazed how the Tuareg do this. They say they follow the footprints of the oldest or slowest camel - and true, sometimes they hobble one to hop around on 3 legs all night, which tends to reduce their range. I guess if you are a cameleer, you quickly develop extremely good eyesight to spot sandy-coloured camels far off in the sandscape and learn how to differentiate your camels' footprints from everyone else's otherwise you'll have a very long walk. Once one is found, things get a bit easier, with an elevated viewing platform from which to spy and ride to collect the others. Miraculously, it never seems to be more than an hour before Al Hadana appears back at our camp leading four roped camels.

Morning breaks on the daily problem of finding 4 camels, which may by now be 5km or more away after their night of browsing. The less the vegetation, the further away they will be. I'm still amazed how the Tuareg do this. They say they follow the footprints of the oldest or slowest camel - and true, sometimes they hobble one to hop around on 3 legs all night, which tends to reduce their range. I guess if you are a cameleer, you quickly develop extremely good eyesight to spot sandy-coloured camels far off in the sandscape and learn how to differentiate your camels' footprints from everyone else's otherwise you'll have a very long walk. Once one is found, things get a bit easier, with an elevated viewing platform from which to spy and ride to collect the others. Miraculously, it never seems to be more than an hour before Al Hadana appears back at our camp leading four roped camels. There's an enormous difference between the camels in a caravan, that plod on tied nose to tail carrying the heavy salt slabs like carriages of a long goods train, and the responsiveness of a racing camel to the slightest movement of the reins. The rather old big camel I've been assigned is a constant-speed plodder. Very well behaved, but no amount of foot-nudging will get it out of second gear!

There's an enormous difference between the camels in a caravan, that plod on tied nose to tail carrying the heavy salt slabs like carriages of a long goods train, and the responsiveness of a racing camel to the slightest movement of the reins. The rather old big camel I've been assigned is a constant-speed plodder. Very well behaved, but no amount of foot-nudging will get it out of second gear!

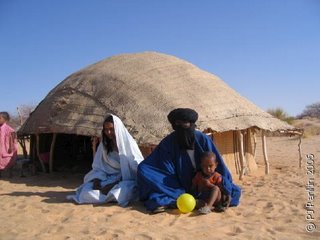

Later we meet Mohamedune's family and his pretty wife cooks a big spagetti bowl for us. (Men only cook when they are travelling.)

Later we meet Mohamedune's family and his pretty wife cooks a big spagetti bowl for us. (Men only cook when they are travelling.) He's proud to show us the fine silver jewelry and ornamental leather work they produce to sell during the short 3-month Timbuktu tourist season.

He's proud to show us the fine silver jewelry and ornamental leather work they produce to sell during the short 3-month Timbuktu tourist season. Once the land the Sahara sands have covered was fertile, with trees, lakes and wild life in abundance, supporting many people as shown in the rock art. Often sea shells or pottery shards from ancient settlements can be found in the dunes. Mohamedune says that sometimes if you are very, very lucky the old pots they find like this might contain treasure - or perhaps a Djinni ?

Once the land the Sahara sands have covered was fertile, with trees, lakes and wild life in abundance, supporting many people as shown in the rock art. Often sea shells or pottery shards from ancient settlements can be found in the dunes. Mohamedune says that sometimes if you are very, very lucky the old pots they find like this might contain treasure - or perhaps a Djinni ? After Moslim prayer prostration on the top of the golden sand dune, silent figures watch the last light of the day. Mohamedune stands, hand-in-hand with his little daughter in a pink coat as big as she is - private time at peace together... Sunset reflections.

After Moslim prayer prostration on the top of the golden sand dune, silent figures watch the last light of the day. Mohamedune stands, hand-in-hand with his little daughter in a pink coat as big as she is - private time at peace together... Sunset reflections.

Al Hadana, the cameleer is our joker, whether noisily imitating Tamasheq ‘rap’, showing off by balancing on one foot on his camel or holding forth around the campfire at night.

Al Hadana, the cameleer is our joker, whether noisily imitating Tamasheq ‘rap’, showing off by balancing on one foot on his camel or holding forth around the campfire at night. Stories run deep in this culture. It’s the way to teach about life in the desert, history, Islam, morals or nomadic customs. Sometimes storytelling is the way to cool meetings between clans in conflict. Sometimes it’s just for pure entertainment on long desert journeys or for whispering in soft Tamasheq around the fire long into the night. Old and young love their stories. There's an old Sudanese proverb: 'Salt comes from the North, gold from the South, money from the land of the white man, but the word of God, holy things and beautiful tales one finds them only in Timbuktu'.

Stories run deep in this culture. It’s the way to teach about life in the desert, history, Islam, morals or nomadic customs. Sometimes storytelling is the way to cool meetings between clans in conflict. Sometimes it’s just for pure entertainment on long desert journeys or for whispering in soft Tamasheq around the fire long into the night. Old and young love their stories. There's an old Sudanese proverb: 'Salt comes from the North, gold from the South, money from the land of the white man, but the word of God, holy things and beautiful tales one finds them only in Timbuktu'. What a surprise to find out that the stories being told around the fire with such delight are just like the old '1001 Arabian Nights' tales! Stories of magic calabashes, serpents, sons with magic powers and princesses falling in love with slaves! The tales are handed down as Tuareg family heirlooms in precious manuscripts written in arabic. In the 14th century, when Timbuktu was the centre of learning of the African Islamic world, all the scholars and teachers came to study and write in Timbuktu. There are still 25000 rare manuscripts in the libraries of Timbuktu, full of legends, poetry, Koranic teaching, early astronomy, medicine and mathematics. Perhaps some of the 1001 Arabian Nights tales were actually written here, then taken back to Persia!

What a surprise to find out that the stories being told around the fire with such delight are just like the old '1001 Arabian Nights' tales! Stories of magic calabashes, serpents, sons with magic powers and princesses falling in love with slaves! The tales are handed down as Tuareg family heirlooms in precious manuscripts written in arabic. In the 14th century, when Timbuktu was the centre of learning of the African Islamic world, all the scholars and teachers came to study and write in Timbuktu. There are still 25000 rare manuscripts in the libraries of Timbuktu, full of legends, poetry, Koranic teaching, early astronomy, medicine and mathematics. Perhaps some of the 1001 Arabian Nights tales were actually written here, then taken back to Persia! Al Hadana tells stories with great energy, kicking showers of coals over Omar or waving his knife to emphasize a point, to the delight of the audience gathered around the fire.

Al Hadana tells stories with great energy, kicking showers of coals over Omar or waving his knife to emphasize a point, to the delight of the audience gathered around the fire.

We stopped mid-afternoon to make camp for the night on some dunes. Just over the rise was one of those amazing ancient scenes you come across in the Sahara, lit golden in the late afternoon. Lines of animals being led by their herders across the sand to an ancient well. Herders wait their turn, each carrying their own worn wooden pulley to put over the wooden axle born by the Y-shaped supports over the well mouth. A boy drives the donkeys out, pulling about 30-40 metres of rope to haul a big leather bag heavy with water up from the depths beneath the desert, to the accompaniment of pulley screeches and donkey complaints. The precious water is then tipped into shallow troughs for thirsty animals to push to get and the donkeys are returned to the well to start all over again. I watched the scene for while and strolled down to the well. One of the herders recognised me from Araoune 4 years ago !

We stopped mid-afternoon to make camp for the night on some dunes. Just over the rise was one of those amazing ancient scenes you come across in the Sahara, lit golden in the late afternoon. Lines of animals being led by their herders across the sand to an ancient well. Herders wait their turn, each carrying their own worn wooden pulley to put over the wooden axle born by the Y-shaped supports over the well mouth. A boy drives the donkeys out, pulling about 30-40 metres of rope to haul a big leather bag heavy with water up from the depths beneath the desert, to the accompaniment of pulley screeches and donkey complaints. The precious water is then tipped into shallow troughs for thirsty animals to push to get and the donkeys are returned to the well to start all over again. I watched the scene for while and strolled down to the well. One of the herders recognised me from Araoune 4 years ago !

Good friend 'Mr. One O'clock' Big Boudjema, whom Bob Geldorf recently featured, is one of those rare desert guides, a true 'pilot du desert'. He can find his way in the 'Azawad' North of Timbuktu, where there is no feature or vegetation in every direction to the horizon's curvature. In such places without reference points the eye becomes confused by scale - a small shrub closeby can appear to be a far off tree. Big Boudj can read the dunes and orientate from the colour, texture and even taste of the sand. He tells the tale of when he was called to try to find three lost cameleers from the salt mines on the Algerian border. Their camels had arrived at Arouane on autopilot without their masters. By following the occasional trace left from the lead camel's rope, they found one man still just alive, but the other two had died of thirst. The rescue party had to mark the dunes to find their own way back. As Boudjema says, you have to remember perfectly in order every single small landmark. Otherwise your tracks will be lost as a dunebug's.

Good friend 'Mr. One O'clock' Big Boudjema, whom Bob Geldorf recently featured, is one of those rare desert guides, a true 'pilot du desert'. He can find his way in the 'Azawad' North of Timbuktu, where there is no feature or vegetation in every direction to the horizon's curvature. In such places without reference points the eye becomes confused by scale - a small shrub closeby can appear to be a far off tree. Big Boudj can read the dunes and orientate from the colour, texture and even taste of the sand. He tells the tale of when he was called to try to find three lost cameleers from the salt mines on the Algerian border. Their camels had arrived at Arouane on autopilot without their masters. By following the occasional trace left from the lead camel's rope, they found one man still just alive, but the other two had died of thirst. The rescue party had to mark the dunes to find their own way back. As Boudjema says, you have to remember perfectly in order every single small landmark. Otherwise your tracks will be lost as a dunebug's.

Passing a little boy riding barebacked by himself with a group of donkeys, I realise that his immediate environment and the local trails through the acacias must be as familiar to him as the streets are back home.

Passing a little boy riding barebacked by himself with a group of donkeys, I realise that his immediate environment and the local trails through the acacias must be as familiar to him as the streets are back home. The constant mantra 'Insh-Allah'- God willing, and their Islamic humility and fatalism are understandable in such an environment. Their code places hospitality to strangers above all else. As they say, next time it could be you seeking help.

The constant mantra 'Insh-Allah'- God willing, and their Islamic humility and fatalism are understandable in such an environment. Their code places hospitality to strangers above all else. As they say, next time it could be you seeking help.

That night is full of wild wind djinnis. Suddenly the wind picks up and howls, buffeting the little round tent. I crawl out into a strange landscape white under a fat moon with acacia trees bending in the fierce invisible blast and sand starting to lift into the air. There's a big heap of the others sheltering behind a bush, blissfully slumbering on top of each other under a big woollen blanket. Thorny branches scratch my hands trying to peg the guy lines. Heaping sand all round the canvas edges, I crawl back into the tent fearing the bending and thrashing tent poles will break.

That night is full of wild wind djinnis. Suddenly the wind picks up and howls, buffeting the little round tent. I crawl out into a strange landscape white under a fat moon with acacia trees bending in the fierce invisible blast and sand starting to lift into the air. There's a big heap of the others sheltering behind a bush, blissfully slumbering on top of each other under a big woollen blanket. Thorny branches scratch my hands trying to peg the guy lines. Heaping sand all round the canvas edges, I crawl back into the tent fearing the bending and thrashing tent poles will break.